The following information is only a “Guide” in order to help current owners and prospective owners. This is not an exhaustive list, but will support the knowledge you need in order to enjoy these cars today.

Bodywork

Today, the most challenging aspect of owning any Mk1 Focus is undoubtedly the bodywork. These cars have experienced their fair share of rust over the years — and in many cases, it started showing up when they were still relatively young. Originally, Ford offered a 12-year perforation warranty, but this was later reduced to 7 years — which may hint at a loss of confidence in the long-term corrosion protection of their vehicles. This issue often stems from a combination of inadequate factory rustproofing, poor paint adhesion, and two decades or more of winter salt exposure.

The outer sills are arguably the most common and problematic area for corrosion on a Mk1. The issue typically starts at the rear of the sills, where water is able to penetrate between the rear sill pinch seam and the inner arch lip. This creates a perfect trap: water collects inside the sill cavity, leading to rust that spreads from the inside out. It’s not uncommon to find Mk1s with visible “patches” welded into the rear sill area.

If left unchecked, the corrosion can spread forward along the sill and eventually affect the inner sill structure as well — turning what could have been a minor repair into a more extensive (and costly) welding job. A quality cavity wax is a must-preventative treatment to minimise and slow any corrosion down.

The inner rear arches represent the second major corrosion area, and it’s a particularly worrying one due to its proximity to critical structural points, including the rear seat belt anchorages. Corrosion often starts around the seat belt mounting points, where water ingress and trapped moisture lead to severe rust over time. From there, it tends to spread along the seam where the inner arch meets the boot floor, weakening the structure and potentially compromising safety if left unchecked.

A major contributor to this issue is the design of the arch liners. Unlike plastic liners found on many modern vehicles, the Mk1 uses carpet-like fabric liners in the rear arches. These absorb and retain large amounts of water, especially in wet or salty conditions. They can stay damp for long periods — creating a perfect environment for corrosion to quietly eat away at the metal beneath the surface, out of sight. This corrosion may even reach the rear strut towers, particularly on hatchback and saloon models. Once it spreads this far, repairs become more complex and invasive.

Despite these trouble areas, it’s worth noting that the majority of the underbody is surprisingly resistant to corrosion, especially when compared to other cars of the same era. This makes it all the more important to target known weak points for inspection and rustproofing.

The main external panels to watch are the front wings which by now if they are the originals will look a little bubbly as a minimum now, especially at the bottom where they bolt to the sills. This area is underneath the main water drain from the scuttle area so moisture is always present in wet conditions! The wings historically bubble where they meet the front bumper due to chafing between the two. Doors can bubble at the bottom front or rear, the seam sealer between the two door skins can fail starting the corrosion.

The slam panel behind the rear bumper can slowly corrode as it’s made of thin gauge steel and it’s only purpose is to cover the rear boot structure. It can only be inspected properly with the rear bumper removed. Front bumpers can sag which is normal as the wing clips which hold them are inadequate for their purpose.

Boot leaks on hatchback models are very common due to multiple areas of water ingress, this could be the seals around the light clusters, seams around the top hatch corners or loose hinge bolts allowing water to creep between the hinge and bodywork. This commonly results in corrosion build up in the spare wheel well and boot-to-floor seams.

In general, the paint on a Mk1 is fairly robust and has held up well over the years — especially on solid-colour models. However, metallic finishes are more prone to issues as the cars age, particularly lacquer peel on horizontal surfaces like the roof and bonnet. This is usually the result of long-term exposure to sunlight, tree sap, and other environmental contaminants that break down the clear coat over time. Once the lacquer starts to lift, there’s no easy fix — a full respray of the affected panels is the only proper solution.

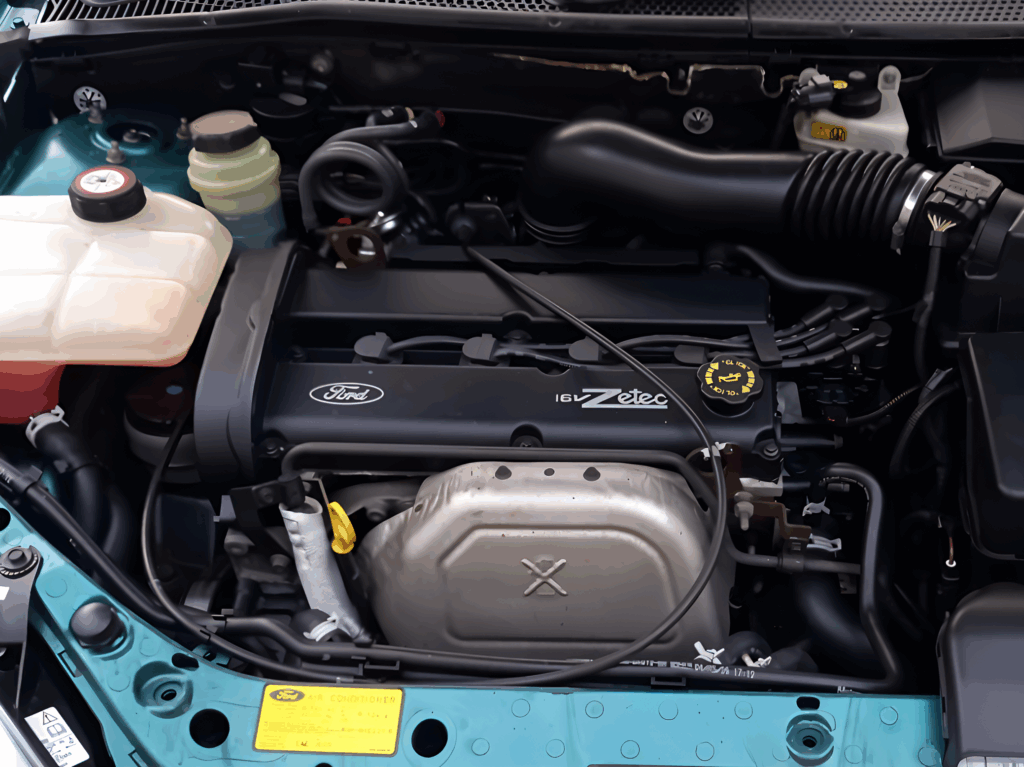

Petrol Engines

The Mk1 came with a selection of durable and well-proven engines, split between petrol and diesel options. Major mechanical failures are rare and usually trace back to poor maintenance or lack of regular servicing rather than design flaws. Service history is therefore important here!

On the petrol side, there are two 16-valve, 4-cylinder DOHC units, both part of the “Family Zetec” engine range. These engines are known for their smooth performance, good fuel economy, and reliability. They’re relatively simple to maintain and can rack up high mileage with ease if looked after properly.

The most common engine found in the Mk1 Focus is the ‘Sigma‘, originally branded as the ‘Zetec-S’. On facelift models, it was rebranded as ‘Zetec-SE’, distinguishable by its plastic cam cover.

This engine was co-developed with Yamaha and Mazda; designed for efficiency, lightness, rev-happy characteristics but with great economy in mind. It was first launched in 1995 with the Fiesta MK4.

Two main versions of the Sigma were used in the Mk1:

1.4-litre (1388cc) – 74 bhp

Found in lower-spec models, the 1.4-litre is often criticised as underpowered, but this is largely overstated. While not brisk, a well-maintained one can still deliver adequate performance around town and on the motorway — especially when driven with enthusiasm. It’s also one of the most economical petrol variants.

1.6-litre (1596cc) – 99 bhp

By far the more common and practical option, the 1.6-litre offers a noticeable step up in torque and usability. It makes the most of the Mk1’s lightweight platform and delivers a strong balance between fuel economy and real-world performance. It’s widely regarded as the “sweet spot” in the range for everyday use.

There are very few issues with the Sigma, namely that lack of servicing and regular oil changes can cause the top end to be very tappety. Equally, running low on oil will quickly cause the bottom end to start knocking. In this last scenario, a replacement engine is advised, as repairing the bottom end is a tricky task due to the fine tolerances in the crankshaft bearing ladder (no torque specs are given). Solid tappets are utilised, which very rarely require re-shimming unless the engine is an extremely high-mileage example.

Timing belts need changing every 10 years by the book as this is an interference engine. Rough running can be traced to a blown breather pipe under the plastic inlet manifold. The right-hand engine mounting is an oil-filled hydraulic one, which can leak oil or partially sink on tired rubber. Another weak area is the plastic thermostat housing, which eventually leaks. Other niggles can be caused by items bolted to the engine, like sensors, where age has caught up more than mileage.

The other petrol engine in the Mk1 line-up is the renowned “iron block” Zetec, officially branded as ‘Zetec-E’. This engine has a rich legacy, having first launched in 1992, and is considered the elder sibling to the more modern Sigma. By the time it reached the Mk1 Focus in 1998, the engine had undergone a significant update and became known as the “Blacktop” Zetec, to distinguish it from the earlier “Silvertop” version. Blacktop revisions brought stronger internals, solid-tappets and a modernised look with a black cam cover.

Two main versions of the Zetec were used in the Mk1:

1.8-litre (1796cc) – 115 bhp

Responsive and flexible, the 1.8-litre Zetec-E offers a slight performance step over the 1.6-litre Sigma without a major fuel economy penalty. It’s a strong all-rounder and a popular choice for those wanting more usable mid-range torque.

2.0-litre (1988cc) – 130 bhp

The range-topping petrol engine in non-ST models, the 2.0-litre Zetec-E delivers a much livelier drive, particularly on the motorway. It pairs well with the chassis and makes for an ideal fast road setup. Despite the performance gains, it remains refined and reliable in everyday use.

The Zetec-E is renowned for being an exceptionally durable and reliable engine in standard form; however, there are still potential problems to look out for. One of the most common is, again, leaking plastic thermostat housings. These mount to the right-hand side of the cylinder head and, with age, warp from heat and eventually crack, a quality replacement is a must. The timing belt needs replacing every 10 years, and proper oil changes will keep these engines running smoothly beyond 150,000 miles.

Another common coolant leakage issue is the heater bypass pipe that runs across the top of the radiator. It’s made from plastic and, again, becomes brittle with age and eventually cracks. Metal replacements for this pipe are available and are highly recommended to prevent this issue from recurring and to provide peace of mind.

The ST170 featured a uprated-version of the 2.0-litre Zetec-E. Branded “Duratec-ST” it came with a Cosworth-designed high-flow cylinder head incorporating continuously-variable inlet camshaft timing; an unique exhaust header, a dual-stage intake manifold, a strengthened crankshaft with forged components and high-lift camshafts. All these changes resulted in an output of 171bhp and 196NM of torque. Rumour has it that more power was possible, but Ford de-tuned this powerplant so it didn’t compete with the RS!

Sitting at the pinnacle of the range is the Focus RS, fitted with the extensively reworked “Duratec-RS” engine — still based on the Zetec-E block but transformed into a serious performance unit. Highlights included a Garrett GT2560LS turbocharger; Forged pistons and WRC-style injectors, uprated intercooler and custom intake system and significantly reinforced internals. This culminated in 212bhp and 229 lb-ft of torque!

The Variable Camshaft Timing (VCT) system on the ST170 rarely causes trouble, as it is a relatively simple mechanical setup. The main item to watch for on RS models is any sign of oil consumption, which may indicate excessive wear in the turbocharger — rebuilds can be expensive.

Diesel Engines

The diesel models are well catered for with a choice of two 8-valve 1.8-litre (1753cc) engines ranging from 75bhp up to 115bhp. Both being Turbo-Intercooled Injection units.

The choice consists of a direct injection turbo intercooled engine, called the ‘Endura DI’ (TDDI). Available throughout production, this is very much a re-development of the earlier ‘Endura DE’ engine found in earlier Fords. This unit utilises a chain driven, rotary style Bosch VP30 fuel injection pump and a fixed vane Garret turbocharger to achieve power outputs of between 75bhp and 90Bbhp (the latter being most common) and proved to be a very popular seller for customers. Providing punchy performance and incredible reliability and longevity.

The Bosch VP30 rotary fuel pump is known to develop issues in certain vehicles, often leading to symptoms such as “limp home” mode, a flashing glow plug warning light, or even complete non-starting of the engine. These problems are frequently traced back to a faulty transistor in the pump control module located on top of the fuel pump. Over time, repeated heat cycles can cause this transistor to degrade or fail, disrupting the operation of the pump. A budget-friendly repair option involves replacing the faulty transistor by soldering a new component onto the circuit board. However, this is a delicate job best performed by an automotive electrical specialist, as it requires precision and experience with electronics.

If the pump cannot be repaired, replacement costs can be significant. A remanufactured unit typically costs around £700, while a brand-new Bosch VP30 pump can range up to £1,400.

The TDCI ‘Duratorq’ was launched in 2001. A revised version of the ‘TDDI’ engine. Available with an impressive 115bhp.This engine utilised a modern high pressure fuelling system called ‘Common Rail Injection’ using electronically-operated Delphi fuel injectors. Alongside this, a vacuum wastegate operated a variable vane Garret turbocharger, creating an incredibly sharp throttle response. This engine is known for its much improved power delivery, refinement and smoothness.

Common faults to be aware of with TDCi engines include injector failure, often caused by the use of poor-quality fuel or neglecting timely diesel filter replacement. Symptoms of failing injectors can include engine stuttering, glow plug light illumination, excessive exhaust smoke, and engine cut-out. Replacement isn’t always cheap—reconditioned injectors typically retail between £80 and £120 each.

Another well-known issue with the TDCI is dual mass flywheel (DMF) failure. Over time, the rubber dampening springs designed to absorb engine vibrations can degrade, leading to symptoms such as; stiff or notchy gear changes, vibration at idle or under throttle or chattering or rattling noises. This can be an expensive repair, with a clutch and DMF kit from a reputable brand often costing over £400—and that’s before labour.

Overall, the Duratorq TDCI engine is an absolutely superb engine choice in the MK1 for the driver who wants impressive torque combined with exceptional fuel economy, smooth and vivacious performance which all in all gives a fantastic driving experience.

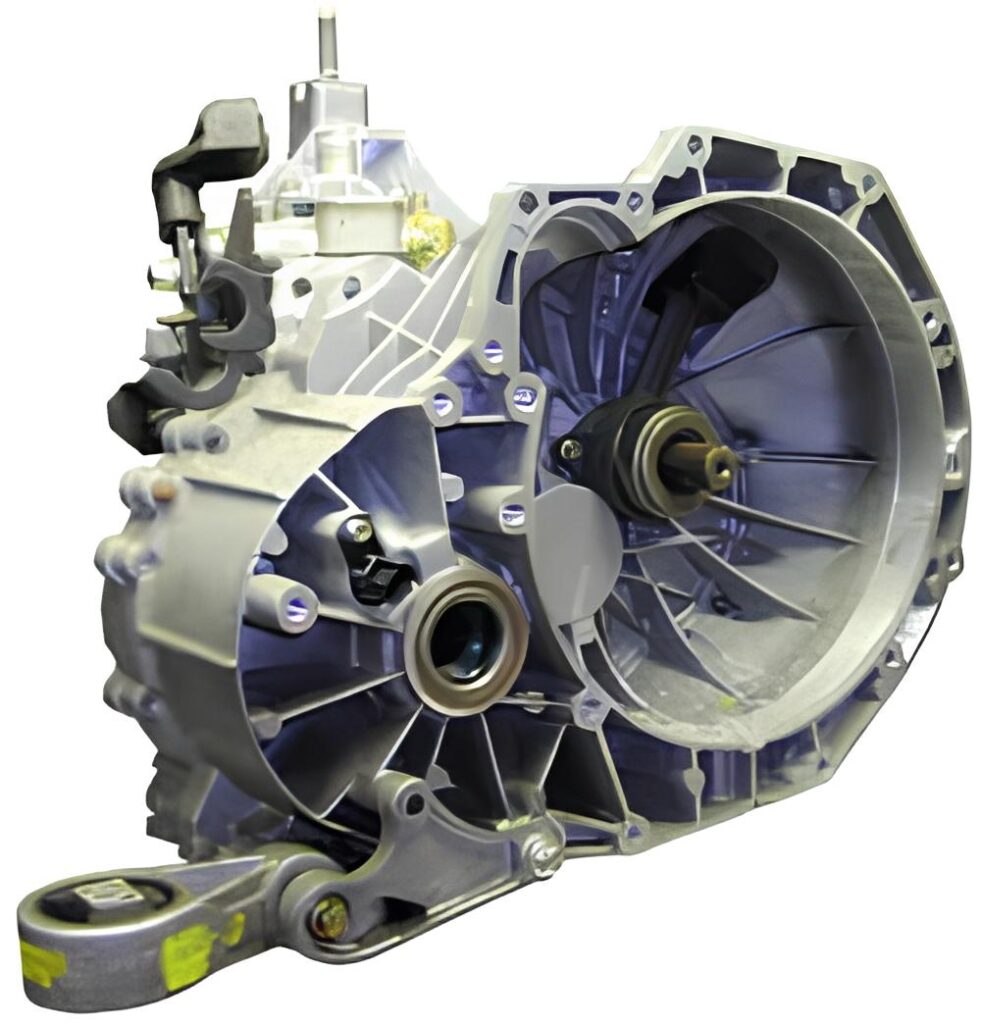

Transmissions

The Mk1 Focus was offered with a range of gearboxes depending on engine and trim level. In general, these transmissions are durable and reliable, with minimal issues when properly maintained.

Whether a five-speed IB5; five-speed MTX75, six-speed Getrag 285 or four-speed 4F27E automatic there shouldn’t be any significant problems – except 1.8-litre Zetec-E petrol models which was also strangely fitted with the IB5. The IB5 is a well-suited gearbox for both 1.4 and 1.6-litre models but when fitted to the 1.8-Litre Zetec-E, it’s at the limit of its torque capacity. So watch out for jumping between gears, difficulty in selection and noisy bearing sounds which indicates a replacement gearbox is in order.

All three manual gearboxes—IB5, MTX75, and Getrag units—were considered “fluid-for-life” by Ford. However, given the age of most of these vehicles, an oil change is now essential for longevity and smooth operation. The IB5, particularly in early models, can be time-consuming to service as it wasn’t fitted with a drain plug (later addressed in the Mk2 Focus). Both the IB5 and MTX75 gearboxes can suffer from sloppy gear engagement or difficulty sticking in gear. These symptoms are often due to stretched gear cables or worn/missing cable-end bushes, which are relatively inexpensive to replace and can restore proper shifting feel and accuracy.

Clutch master cylinders and concentric slave cylinders are made predominantly out of plastic, both give minimal long-term issues but will are now starting to leak with regular occurrence, an awkward job on the master! Clutch release bearings that are built into the concentric slave can get rough and sound growly when the clutch is depressed. Changing this when changing the clutch is a must!

The 4F27E is a Mazda-designed four-speed automatic transmission known for its smooth and progressive gear shifts. It’s generally a reliable unit, with major failures being rare. The most common issue tends to be solenoid failure, which can result in loss of certain gears or poor driveability. Fortunately, this is a relatively straightforward repair, and solenoid and filter kits are readily available. A solenoid replacement paired with a fresh fluid and filter change is often enough to restore normal operation and can be carried out for a reasonable cost. However, on higher-mileage units (typically over 100,000 miles), there is a risk of internal pressure loss due to leaking clutch drum pistons. This often leads to a loss of reverse gear, which is a sign of internal hydraulic issues. If this occurs, the most cost-effective solution is usually to source a replacement gearbox for around £500—significantly cheaper than a full transmission rebuild.